Don’t people listen to science (any more)? Why don’t they act in their own best interest? If people don’t act, they don’t care, right?

Intractable problems are “wicked” because even effective education and motivation don’t budge them. Thankfully, science offers a solution: we must identify and enable vital behaviors. My PhD research reveals this to be a key building block of transformation.

NOTE: the content is the same whether you read or listen!

Image credit: carmen6969 from Pixabay.

Let’s debunk another myth about change

If knowing what is right and good were enough, we’d all be healthy, happy, and buoyed by nurturing relationships.

We accept that endlessly restating the desired outcome is not enough in athletics, weight loss, or family dynamics. So why do we insist — and use it to justify our despair and the othering of others — that it is enough in changing complex systems?!

Building on my metaphor of systems change as a house move: what exactly will it take for our possessions to get from Point A to Point B, perhaps with stops at three different charities to drop off what we no longer need as well as an offload of some keepsakes into self-storage?

Want to change the world? Master systems thinking

One of the most common mistakes when targeting transformation is failing to consider the complex system hosting the object of our discontent (aka the element we wish to change). We dig ourselves deeper when we imagine direct causality from our actions, and deeper still when we focus exclusively on their object.

Transformation demands changing habits

Our habits are a solution to the complexity of life. Habits remove the need to consider the full range of options for the hundreds of decisions we must make every day.

However, most of our habits have become a liability because they create outcomes we no longer want.

To recast the world for the better, we must retrain ourselves across every sphere of life, and that is not going to happen by pep talk alone.

You may think your change is technological, but it still demands that a person opens a different application when required and uses it as intended. Similarly, a policy change or a change to the building code ultimately means that a great number of professionals who do not know each other, communicate, or organize do something differently tomorrow.

Whatever change you seek, it comes through a specific change — or a set of changes — in human behavior.

We set ourselves up to fail — and we must stop

We would not imagine the Olympics to represent the peak of athleticism if we qualified athletes by merely throwing a bunch of motivated people into a stadium. We select promising candidates and then methodically train them in the exact winning techniques until those become their second nature.

A good coach wouldn’t imagine telling a sprinter over and over again to be faster off the blocks. On the contrary, she would home in on the exact behaviors — where the athlete sets their feet, how they distribute the weight to their fingers, etc. — and focus her training on those nuances, requiring that they be practiced over and over in non-stressful environments before the stakes creep up. So, how come we think we are fabulous at changing culture just for telling people the outcome of the change we want?

Understanding what change means to your people

Think about each of the populations impacted by the change you seek and consider what exactly differentiates their behavior in the “future state” from what they do now.

Case study: Reinventing a media company’s ways of working

Headquartered in Australia, this media company spanned some 400 locations around the world. During a critical time in this organization’s battle on the changing media landscape, I was asked to help craft the business case for transforming how it worked; a solution that had to include greater performance at dramatically reduced costs.

Once the proposal was approved by the Board, I was responsible for the design and implementation of the requisite transformation. My scope included stakeholder engagement, communication, change management, training development and delivery, evaluation, reporting, and micro-innovation to an extent that I had never before experienced nor been accountable for.

Like in similar cases, the biggest cost savings would come from significantly reducing the organization’s total office area. So, the program was spearheaded by the head of property with direct support from brilliant architects. This transformation, however, involved a comprehensive and technology-driven change in the ways of working (from a clunky mishmash of software to the Google suite) and a restructure that would lead to massive layoffs. This program was my closest collaboration with IT (information technologies) and HR (human resources) teams at the time, and it informed many of the what I now pose as the building blocks of transformation. The fact that remote and activities-based work has since become commonplace for many of us hopefully helps makes these examples more salient.

How to identify vital behaviors

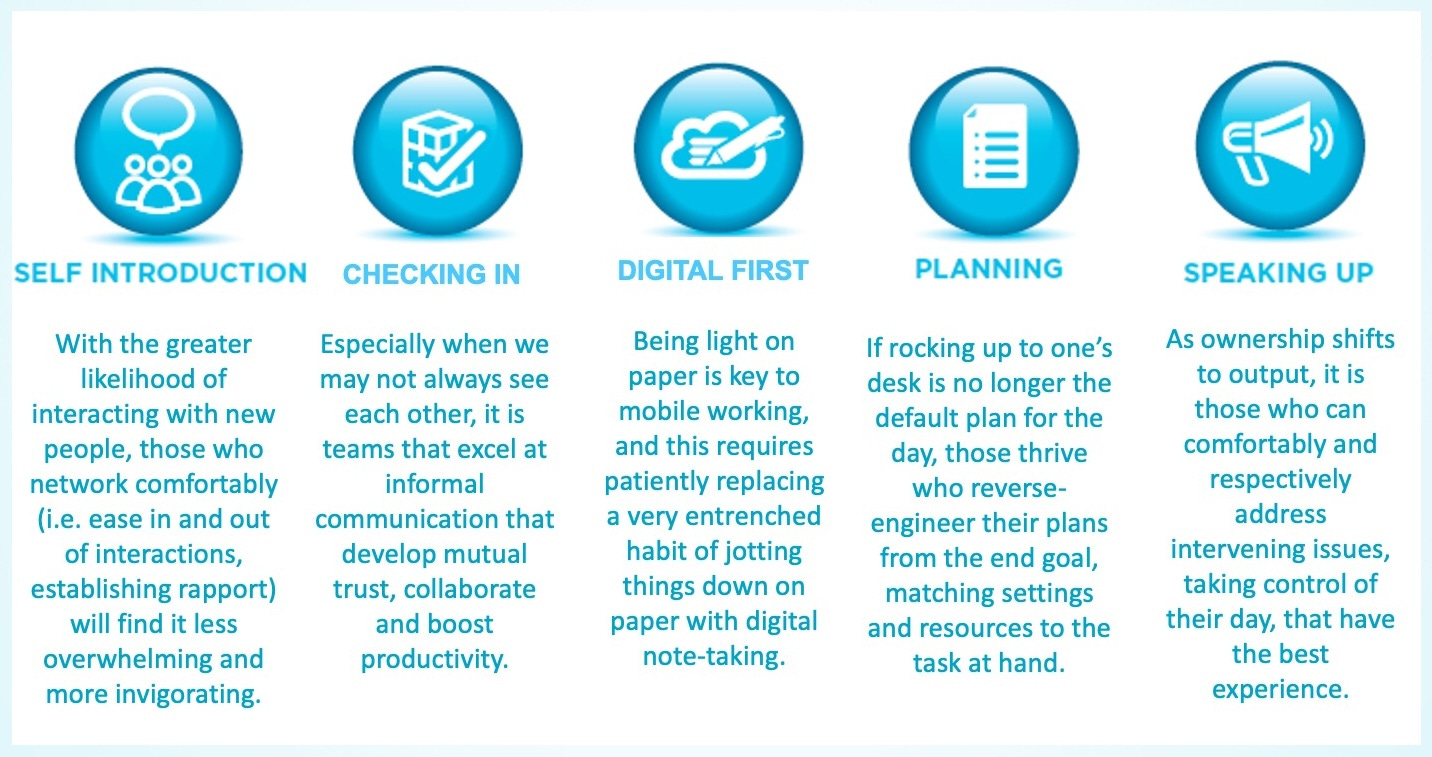

Using what is called positive deviance, a methodology for evaluating why an otherwise prevalent problem does not occur in a certain group of people, I observed teams that did not report the problems associated with activities-based working (ABW) that tended to sound like, “I feel unsafe,” “I feel isolated,” “I don’t know how to get help,” and “I can’t get attention for the decisions I need made.” I identified five behaviors, and one stood out: those who did not have the above problems in ABW environments were comfortable introducing themselves. This may seem irrelevant but imagine connecting with a busy-looking person you have never met, let alone asking them for help, if you can’t do this.

I distilled this vital behavior into four segments:

Skill #1: Initiate dialogue. “May I please interrupt you for a second?” or “May I join your conversation?” or even (this tactic combines #1 and #2) “I set myself the goal of meeting new people today, so I hope I can meet you if you excuse my awkwardness.”

Skill #2: Establish rapport. This can be achieved by sharing something personal (for example, “I am new and excited and don’t know all the rules yet”) or by evoking something about the person you’re engaging (for example, “Hey is that adorable pug yours? I have three!”).

Skill #3: Ask for what you need.

Skill #4: Exit the dialogue. This last segment proved curiously important. Have you ever been at an event where you regret starting banter with a person because ten minutes later, you have heard everything about their children, hobbies, and cats, and your only way out is to fake needing to use the restroom? As such, I found that it was this skill that most stood in the way. So, I drafted a few “outs”, and we co-created a dozen more. Curiously, authenticity was often preferred, for example, “Hey I don’t want to offend you, but I also need to keep moving through the room.” Ever since that experience, I suggest multiple ways to get out of a conversation whenever I train younger professionals in networking. The key, however, is practicing “the out” when getting it wrong is inconsequential. Which is what we did for the media company in multiple gamified sessions.

The other four behaviors deemed vital for that transformation were “checking in”, “planning”, “pen to cloud”, and “speaking up.” Each was mapped and trained with the same level of rigor.

The behavior change program I subsequently designed for the media company had everybody practice these behaviors in playful settings. Furthermore, we normalized it by printing their swanky icons on mouse pads, posters, screensavers, and more. An example of how graphics can take on the load of change comms.

Recovery behaviors are just as vital because they help us get back on track

I would be remiss to talk about vital behaviors without drawing attention to recovery behaviors. Recovery behaviors are how we get back to what we are supposed to be doing when we, inevitably, lapse into how we used to behave. Sobriety is one analogy I can offer here. Even after 38 years clean and sober, my extraordinary wife would explain sobriety as a day-at-a-time journey. At any point, you may be tempted. And every point is a chance for a recommitment to what you have chosen for yourself.

In defining vital behaviors, plan for imperfection and define recovery behaviors.

For sobriety, the recovery behavior is to stop at whatever point. Leave the substance at the checkout counter, ignoring the clerk. Turn around even as your friends walk into a bar. Pour out whatever remains in the glass. Drop everything and find an AA meeting. While the difficulty of self-introduction may pale in comparison to battling addiction, a recovery behavior for self-introduction may go something like, “Hey, I am freaking out… I have been disoriented all morning because I couldn’t bring myself to introduce myself to a complete stranger when everybody looks so busy. However, it is never too late to start, eh? Would you please let me introduce myself and meet you?”

The take-away

In whatever change you seek, you need to define — as meticulously as a tennis coach would pinpoint the precise angle of a player’s wrist — what change is required. Like with the tennis player, it is gravely insufficient to think that understanding, motivation, or even the number of reps suffice by themselves. In fact, a coach who merely repeats why a player should do better isn’t staying in business long. Behavior is key here. What exactly is a person doing differently in that future scenario where your solution exists?

Further reading

In my practice, the seminal expertise on vital behaviors and on how to enable them (the next building block) is best captured in Grenny et al’s Influencer (2013).[1]

To see how this building block fits into your entire roadmap to impact — from identifying your transformational ideas through vetting, funding, implementing, and scaling them to putting yourself in the best position to thrive — get your copy of Change-maker’s Handbook (2023).

[1] Grenny, J. et al (2013). Influencer: The New Science of Leading Change. McGraw-Hill Education.