One of the most common mistakes when targeting transformation is failing to consider the complex system hosting the object of our discontent (aka the element we wish to change). We dig ourselves deeper when we imagine direct causality from our actions, and deeper still when we focus exclusively on their object.

Any transformation strategy that stands a chance reflects systems thinking. In fact, systems thinking is one of the key skills for changemakers to master, as revealed by my current PhD research into changemaking. I will be sharing a lot more of my findings soon, so stay tuned!

Is this going to scramble my brain or put me to sleep?

A key problem is that the body of knowledge on the topic is — to put it very mildly — dense. The look and heft of books on systems are enough to put one off trying.

I have been told that my explanation of complex systems allows people to understand the concept for the first time. In case that is even a little bit scalable — and might also help you explain this to others — I’d like to share how I make sense of systems theory and apply it in creating regenerative transformation at project, organization, community, and industry levels.

What is a system?

The term “system” refers to a cohesive group of interrelated, interdependent components that is more than the sum of its parts. The interdisciplinary study of systems is called systems theory, and an inquisitive mind will find no lack of curiosities there.

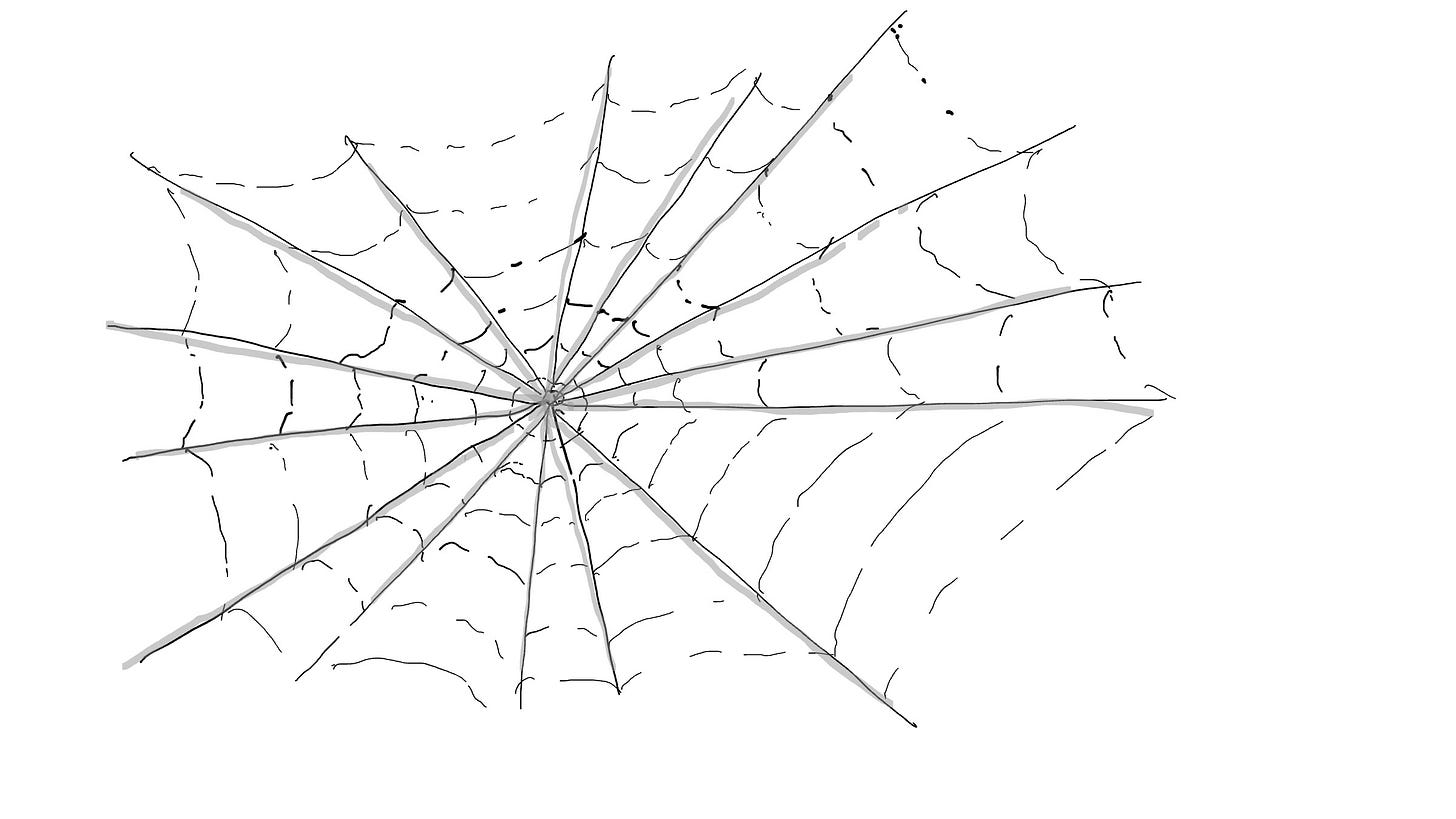

Systems are spider webs, not Jenga towers

Have you ever tried to free anything from a spider web? Unlike removing a loose block without disturbing the rest of the Jenga tower, pulling on any part of a spider web stretches and distorts the entire structure. If you let go, the web springs back to its original state. Similarly, it is futile to cut out a small piece of the web: it will take no time at all for it to be patched over.

Image credit: Elena Bondareva

Key points about systems thinking

Here are the take-aways from the spider web analogy:

Complex systems are coherent. An elegant and efficient response to their context and function, they make sense, even if not to us.

Complex systems are self-organizing. Countless elements respond to their context in self-interest, remaining in flux until they find equilibrium.

Complex systems are stable. Once they settle, they like being just the way they are (our opinion is, again, utterly irrelevant). The stability of systems doesn’t mean they work serve all equally well. Rather, it is a confirmation that all the elements have been reconciled.

Complex systems are resilient. A single action is no more likely to change a system than a pebble is to change the shape of the pond for more than a fleeting moment. The pond surface stills; the spider web springs back. Transformation is similarly vulnerable to “reverting to type.”

Complex systems are nested within other systems. Like those in a human body, systems (such as the cardiovascular, respiratory, nervous, digestive, and others) work together, and a failure of one can compromise the others. Similarly, an attempt to change one system may be sabotaged by the other systems.

Complex systems blur, if not outright mangle, causality. We cannot control or accurately predict the impact that any one change may have on other components or on the system as a whole. If it heals properly, a broken bone is stronger than an intact one. Could you credit an element of your character to a single cause? We’ll pick this up when we talk about measuring impact.

What systems thinking means in practice

I had the chance to experience these principles vividly when co-leading a traveling studio with the extraordinary Dr. Dominique Hes and Dr. Chrisna Du Plessis. That studio brought interdisciplinary cohorts of Masters students from the Universities of Melbourne and Pretoria together in South Africa to design place-based interventions to observed problems.

One group wanted to address the routine flooding of a path, which was the result of a leaking pipe. The proposals to patch the pipe and to raze the path both seemed logical enough. That is, until the group mapped the likely impact of both interventions on the broader system that had evolved, over what could have been years, around this “problem.” Households and stray animals alike relied on this accidental creek for drinking water. Countless plants thrived with the extra moisture, providing habitat and food to many species of bugs, which in turn fed frogs and birds. Over the years, the flooded segment had sprung a whole network of paths; some were even paved.

While the gush from the busted pipe would have been a disruption when it first occurred, over time, the complex system absorbed it to the point that it felt crude to prefer the “before” to the “now.”

In determining whether they should intervene, the students got to appreciate the stable and content system where somebody depended on its every nuance, even if flawed to our naked eye.

Given how desperate our world is for transformation, don’t you wish we were all taught systems thinking?

Systems thinking and the 3d law of motion

While much less linear, transformation, in a sense, follows the laws of physics: for every action there must be an equal and opposite reaction. Thus, a transformation strategy is as effective as its ability to understand the entire system it is trying to change and apply the right amount of effort at every likely point of resistance for as long as it takes for the system to contently stabilize within the new parameters.

Systems thinking is like a house move

In this, a transformation strategy is like a quote for a house move. The moving company would match the vehicle(s), packing material, and support personnel to the volume and mass of the load, accounting for any of its irregularities and fragilities. You may need to move a few boxes (and a hand cart will do), a moderate but oddly shaped load (for a truck), or several fragile truckloads. The next level of complexity is the distance that load needs to travel.

Unlike possessions, however, transformation — like a spider web — doesn’t like to stay where you take it. It is one thing to make the change happen. It is a whole other challenge to get it to stick. In that sense, this work is perhaps more like relocating domestic cats than boxes: if you’re not mindful, you may find them somewhere along the way to their old home. So, when planning change, we must manage the additional risk of it all reverting to type. Which is why embedding change across systems, people, and technology must form an essential part of every transformation plan.

Yep, I have or will cover all of these aspects in this Substack!

We are products of complex systems

However tidy in sound bites, even our origin stories are complex. Sure, a single event may have fueled your motivation to become a teacher, a physician or a pilot, but it was not crowded out by equally compelling experiences that would have steered you in another direction. Furthermore, your desire was sustained by your environment, even if barely, and nurtured by training. And this is just the complexity I can fit into a paragraph.

We — just like our environments and social structures — are products of countless external influences, actions, and inactions, as well as internal factors that start with genetics and weave through every decision and indecision that, jointly, land us on the threshold of an opportunity as well as inform how we respond.

It is the appreciation of complex systems that has left me with an aversion to the term “self-made,” which I discuss in Section 5 of Change-maker’s Handbook (2023)

REFLECTION

These questions might help you apply this post to the change you’re looking to make in the world.

What is the system you’re trying to change?

What other systems — like the many that govern our bodies — interface with this system in focus?

What is enabling/perpetuating the problem you’re trying to solve?

What might depend — downstream — on that problem remaining unsolved?

What might it take to recalibrate the system to solve that problem?

Let me know how this resonates and ask any questions you might have!

Share this post